Madagascar — a place like no other

by John C. Deppman, Fort Meyers, FL (Part 1 of 2)

I always considered Madagascar to be a dream travel destination, and I fervently wanted to visit the island. Having taken previous ecotours to West, East and Southern Africa, I felt I was ready to take on this big island.

A unique destination

The fourth-largest island in the world, Madagascar follows only Greenland, New Guinea and Borneo in size. At 227,000 square miles, it is larger than California, and because of the great distances involved it is necessary to fly to see the various regions of the country.

Driving great distances in Madagascar isn’t practical because once one leaves the capital city of Antananarivo, called Tana by almost everyone, the roads deteriorate greatly and the pace of vehicular travel becomes snail-like due to potholes, deep ruts and sand dunes in the road.

It is generally believed that the island broke away from the African mainland about 165 million years ago and from the Indian subcontinent some 80 million years ago, and to this day it has remained disconnected and remote.

The evolutionary process at work in such an isolated tropical environment resulted in the biodiversity that exists today. Furthermore, since the country itself is mountainous throughout the entire interior, separate ecosystems have evolved in the various regions of Madagascar.

Planning the trip

After checking out several companies that have experience conducting tours to Madagascar, I settled on Naturetrek (Cheriton Mill, Cheriton, Alresford, Hants, SO24 0NG, U.K.; phone 01962 733051).

I joined their trip to Madagascar in October and November 2003. It was advertised as “a 23-day wildlife holiday in search of the unusual birds, plants and mammals of the forests of Madagascar.”

The cost of the trip was £3,390, or about $5,800. This included the round-trip flight on Air France from London Heathrow to Antananarivo (via Paris), three internal flights on Air Madagascar, all accommodations and meals, local transport, and international and local guides. The only extra items were souvenirs, drinks, tips for the local guide and, of course, getting to and from London.

I had traveled with Naturetrek three times before this trip, and two of the holidays (to Kazakhstan and the UAE) had been excellent. The third trip (to Peru) had been poorly organized, but the company assured me that the leader for the Madagascar trip would be well qualified, which proved to be the case.

Our group of 12, all from the U.K. except me, was an even mix of men and women with ages ranging from roughly 40 to 70. Our goal was to see as many different species of birds, lemurs and plants as possible while not overlooking whatever else nature had to offer, such as chameleons, frogs, lizards and moths.

Madagascar has a high degree of endemicity amongst its flora and fauna; as a result, remarkably unique birds, mammals, reptiles, insects plants and trees can be found there.

In order to accomplish our goal in a little over three weeks, we visited five different habitats scattered around the country: Berenty Private Reserve, Ranomafana National Park, the spiny forest at Ifaty, Ampijoroa Field Station and Andasibe-Mantadia National Park.

Berenty Private Reserve

After spending the first night in a pleasant hotel in Tana, the Hôtel du Louvre, we flew to Fort Dauphin at the southern tip of the island, then drove west for about three hours by bus to Berenty Private Reserve (visit http://taniko.free.fr/parks/berenty.htm for more information on the park).

This is one of the better known and more popular wildlife-viewing destinations in Madagascar, for it is here that several species of rare lemurs and birds can be seen with relative ease.

It is privately owned and operated by the de Heaulme family. The individual bungalows are relatively clean, with en suite shower and toilet facilities.

Driving into the compound, we were greeted by about 20 ring-tailed lemurs prancing and capering about the premises and paying very little attention to us. Of course, this is one of the main reasons to visit Madagascar, for lemurs in the wild are found nowhere else on Earth. Although ring-tails are rare, they are plentiful at Berenty.

We saw several types of lemurs here, but the most fascinating had to be the Verreaux’s sifaka. Overall buff in color, with a little black nose and black on top of its head, it would cling to a slender tree trunk and gaze at us. Then abruptly it would leap to the ground and “dance” on its hind legs to another tree.

Sifakas are well known for their “dancing,” a sort of sidewise, bouncing hop, and it’s a delight to watch them.

Wildlife viewing

We spent three days at Berenty walking through both spiny forest and gallery forest in search of lemurs and birds. We saw a Madagascar ground boa curled up next to a tree and were happy to learn that none of the snakes on the island are poisonous, although the boas are constrictors.

On the second day we saw Madagascar flying foxes. With wingspans of over four feet and furry bodies that look very much like a fox’s, plus their bat wings, they are amazing creatures.

The wide and level red dirt paths through Berenty’s forest made for pleasant walking. On the walks we saw many of the endemic bird species, including the white-browed owl, the Torotoroka scops owl and the souimanga sunbird. Sunbird species, which are found throughout Africa, the Middle East and Asia, are always fun to observe. They correspond to the hummingbird, which is found only in the Americas, but they are a little larger.

We also met primatologist Alison Jolly, author of “Lucy’s Legacy” (1999, Harvard University Press), an erudite but quite readable book on the subject of evolution. She was studying the behavior of ring-tailed lemurs and spoke with us about her research.

A whale? Where?

After our stay at Berenty Private Reserve, we drove back to Fort Dauphin to spend the night before our flight back to Tana. We had time in the morning to walk across the road to the sea for a whale watch. I had never been on a whale watch before, either by land or sea, so it was all quite new to me.

We found an excellent vantage point on a hill overlooking the Indian Ocean and were all poised with our binoculars while three people with spotting scopes scanned the distant horizon. Someone excitedly exclaimed, “I see one. It’s blowing.”

We all looked in the direction he indicated and others joined in: “Look, there is the fin.” “It’s blowing again.”

It was clear to me that everyone was looking at a whale, but after examining over 100 whitecaps, each one temporarily appearing whale-like, I could not see it.

The time came for us to leave, and as we were packing up, the leader cried out, “It’s up! The tail is up!”

I looked through my binoculars and, yes, indeed the tail was up! Even I could see that. My first humpback whale!

Ranomafana National Park

From Tana we undertook the long drive south to Ranomafana National Park (visit http://info.bio.sunysb.edu/rano.biodiv/index.html for useful info). This park is popular for ecotourism because the rainforest contains a large variety of birds and lemurs.

The paths through the forest are hilly but rewarding. It was here that we saw such rare birds as the brown mesite, the velvet asity and the white-throated oxylabes, as well as the distinctive and vocal cuckoo roller, a bird not closely related to any other species.

But the real charm of Ranomafana is the lemurs. All three species of the gentle bamboo lemurs live here and, with the assistance of our local guides who were able to spot them for us, we saw them as well.

On the way back to our bungalows we uncovered a mantella frog, a small frog that was all black with lime-green legs, reddish-orange feet and spots underneath. Remarkable in appearance, it is similar to the poison dart frogs found in Costa Rica.

A night out

One evening just after it became dark, we took a night walk. Armed with flashlights, we climbed the trail into Ranomafana in search of nocturnal lemurs, shining our lights into the trees hoping to see the reflection of little eyes. The walk was guaranteed to be a success because every evening the park rangers place bait (mashed bananas) on some trees and shrubs in a small clearing.

This attracted delightful little brown mouse lemurs, lively and mouse-like in size and appearance except for their long tails and large eyes, useful for night vision.

We even saw a fanaloka, or Malagasy striped civet, a shy, nocturnal, cat-sized mammal that appears somewhat like a short-haired brown fox with stripes comprised of black dots on its back.

Rainforest accommodations

While visiting Ranomafana National Park, we stayed for three nights at Hôtel Domaine Nature, which has 15 individual bungalows built on the rainforest hillside. The bungalows are rustic but entirely adequate, and from my window I could almost reach the bananas growing just outside.

During my stay there, I had four large, beautiful moths on the outside of my door. They ranged in size from the old-fashioned silver dollar to twice that size and I only knew they were alive because every day they would be in a slightly different position on the door.

Isalo National Park

It is a 2-day drive across the island to the west coast, so we broke the travel time up by spending two days in Ihosy at Le Relais de la Reine, a first-class hotel seemingly in the middle of nowhere.

Nearby Isalo National Park is the most popular park in Madagascar, due primarily to its spectacular scenery. After the one-hour climb to the top of the Isalo massif, hikers are rewarded with breathtaking views of the gorges and gullies below.

On the way up, we saw Madagascar periwinkle growing in the rocky fields along the pathway. This plant, with a beautiful little rose-colored flower, is now internationally famous as a source of the anti-cancer alkaloid vincristine, which is used in the treatment of childhood leukemia.

On toward the coast

After spending two days investigating Isalo National Park, we continued on toward the west coast of Madagascar, stopping briefly at Zombitse Forest to search for the skulking bird known as Appert’s greenbul. Globally threatened and quite rare, this lackluster little fellow can be found only here.

Then we continued westerly, passing through the town of Ilakaka, if indeed it can be called a town. Ilakaka cannot be found on most maps because it did not exist six years ago.

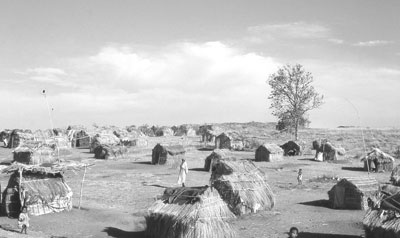

The first sapphire was discovered there in 1996, and the feverish rush began in 1998 when the existence of high-quality sapphires became known to the public. There is now a gold-rush feeling about the place, with some 10,000 adventurers, gem traders and other fortune seekers living in close, makeshift quarters hastily constructed of tin, bamboo and straw.

Once in the Tulear area on the southwest coast, we spent two nights at Le Mangrove Hotel in Anakao. Located right on the Mozambique Channel, the hotel is convenient for a day trip by boat to Nosy Ve, a small island with sandy beaches and ideal snorkeling.

The wildlife highlight here was seeing the nesting red-tailed tropicbirds. Stunning all-white seabirds with red bills and long, thin, red tails, the females were roosting under small shrubs, well hidden from any airborne predators such as hawks or eagles. The females were often with a young one nearby, while the males were flying about bringing in food for them. We appreciated them from a distance so as not to disturb them.

Leaving Anakao, we drove north from Tulear to Ifaty, also on the coast of the Mozambique Channel. Although not far as the crow flies, it took us almost three hours by bus due to the sandy, rutted road. This was an entirely different habitat: the spiny forest.

Next month the author explores Madagascar’s spiny forest, as well as the Ampijoroa Field Station and Andasibe-Mantadia National Park, as he concludes his journey.