The Philippines — sophisticated city life plus a taste of the tropics

by Steve Venables, Contributing Editor

Don’t get me wrong. I had been to the Philippines before and loved the place, but faced with an invitation to visit again in February-March ’03, the decision was not easy. Years of tentative governments, guerrilla warfare, kidnappings, terrorism and charges of graft and corruption have been no stranger to this part of the world. Had things gotten worse, perhaps seriously dangerous?

The U.S. State Department had put out warnings, plus America had begun its war on terrorism and armed conflict with Iraq was imminent. I checked with a travel risk assessment service* and found that on a scale of one to 10, with one being risk free and 10 being too risky to visit, they ranked the Philippines a nine. What to do?

Looking back

My first real visit to the Philippines was in July 1985, for nearly two weeks. One of the things I remember most were the stars. On a clear, moonless night on a remote island, looking up from our resort’s beach I saw more stars more brilliantly than I ever imagined possible. It was utterly magical.

Another touching memory from that trip was our group’s visit to one of the 300 islands of Tawi-Tawi, off the Zamboanga Peninsula. Apparently, few American travelers had bothered to visit this southeasternmost area of the Philippines since WWII, and when the island’s people heard our group was coming, they let the children out of school, gave them American flags and lined them up along the roadway to wave the flags at us as we paraded slowly by jeep into the main town.

I felt like we were masquerading as heroes and was certainly puzzled as to why we deserved such a joyous welcome. But, of course, we represented far more than ourselves.

The town held a ceremony on the steps of its library, where the mayor greeted us as the brothers, sisters, sons and daughters of the soldiers who had been there before, with the hope that we were the vanguard of a wave of returning Americans who would one day happily splash ashore and bring the island improved prosperity through tourism.

Sadly, despite its pristine beauty and potential for ecotourism, the country’s location in a troubled area still prevents it from being a popular place to visit.

With these and other fond memories, I decided the Philippines was worth seeing again.

Getting settled

Our group arrived in Manila just as the sun was coming up. We had flown overnight from San Francisco and lost a day crossing the international date line. Our total travel time, including a Honolulu stop, was about 16½ hours.

The weekend morning traffic into town was scant, so our ride was quicker than I had expected. The airport properties gave way to a dilapidated residential area comprised of cinder-block shacks roofed with rusting corrugated metal or plastic tarps. Abrubtly, modern highrises rose up as we entered the city suburb of Makati, once a swamp but now a prosperous business center with attractive hotels, apartment houses and shopping centers.

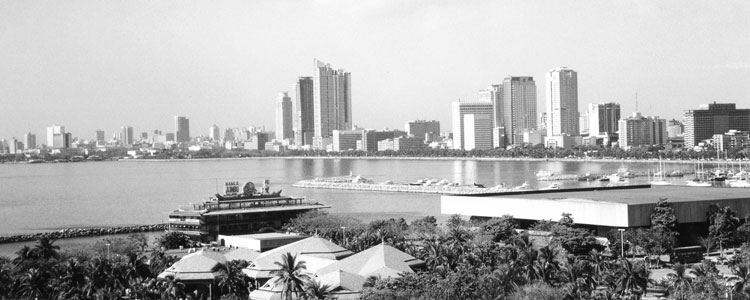

Metro Manila is made up of 13 cities and four municipalities, covers 636 square kilometers and has a population of over 15 million. (Singapore has about the same amount of land but only three million people.)

Our first hotel was indeed attractive. Located in the center of Makati near the Philippine stock exchange and across from the Ayala Center shopping malls, The Peninsula Manila (phone 63 2 887 2888) caters mainly to business travelers.

With rates starting at nearly $300 per night plus tax and service, it has 498 rooms and suites in two 11-floor towers, plus a ballroom, meeting rooms and a 24-hour business center. For about $100 more a night, the business club level includes extra services and features designed to make those traveling on business comfortable.

For the other 10% — guests not traveling on an expense account — there are deals. A quick check after I got home revealed seasonal rates as low as $95 a night for a superior, city-view double room.

Getting a taste of the city

Fifteen minutes from our hotel, we had our first lunch at the Kamayan Buffet (523 Padre Faura). When Kamayan, which means “by hand,” opened, everyone was expected to eat by hand and no utensils were ever available. Open troughs with running water from jugs lined the walls, so you could wash your hands after each course. Now, however, utensils are available.

Their special “no leftovers” price was 275 pesos (about $5), but if you had leftovers on your plate the price jumped to “all you can eat” for $12. Undoubtedly, I was stuck with the second price, since there was a lot and most of it was pretty exotic, in my book. My impression was that this was a local hangout.

After lunch we visited the small Ayala Museum, located on the third floor of the Glorietta No. 2 shopping mall. It was worth an hour to view the handcrafted models of native outriggers, Chinese junks and Spanish galleons, plus the history of the Philippines, from its first settlers through the Spanish and American periods, displayed in dramatic diorama form.

This museum is being moved and is expected to open at a new site on Makati Avenue in 2004.

Remembrances

Our next visit was to the Manila American Cemetery and Memorial, about six miles southeast of Manila’s city center, in Fort Bonifacio (formerly known as Fort McKinley). The 17,206 Americans killed in New Guinea, the Philippines and other islands of the Pacific during WWII were moved from temporary sites and reburied here, making it one of the largest American war cemeteries outside the U.S.

The site covers 152 acres and was designed by Gardener A. Dailey of San Francisco. White crosses and Stars of David are arranged in concentric, curving rows on green lawns, forming kind of a gentle amphitheater facing Manila. The memorial is at the hub, inscribed with the names of 36,285 missing Americans who served in our armed forces during 1941-1945 — a sober yet proud tribute to those who gave their lives.

Our last visit of the day was to Manila’s National Museum. Its first room contained the scattered remains of the Spanish ship San Diego which, while trying to sail from Manila to Acapulco on Dec. 14, 1600, was sunk by a Dutch ship one-fourth its size. The ship’s artifacts, such as cannons, tableware, jars and her wooden skeleton, were finally recovered from the sea in 1991.

There is also an interesting gallery of 45 or so oils on canvas dating from 1900 to about 1975. On the second floor you’ll find a history of five centuries of maritime trade and on the third floor, a nice collection of porcelain, mostly Chinese.

Mixing with the locals

I like to walk in the morning before breakfast. The streets are still quiet, the air is fresh and I find time to form impressions of the town and its people without the bustle and jostling found later in the day.

Here, with my European-American face, people were sometimes startled, and often I caught them doing double takes. I’d just smile, and guess what? They always smiled back. If there’s one characteristic I’d like to apply to the Philippine people, it’s that they are not stingy with their smiles. A couple even greeted me with “Hi, Joe!” — a friendly leftover from WWII.

After breakfast, we went out on the town to check out the shopping. The Philippines is a definite alternative to Hong Kong and Bangkok as a shopping destination, provided malls are your thing. The first one we visited, the Power Plant Mall in Makati, had no public transportation access, so even though Manila has 40% of all the Philippines’ cars packed onto 2% of the country’s roads, it is still inconvenient for many.

With mostly upscale stores, you’ll see handsomely dressed little children, each escorted by their own personal, uniformed nanny. The place was not really meant for souvenir shopping and was kind of a bust, for me. But the Glorietta Mall, across from our hotel, was everything one could hope for. Actually, it is not one mall, but several — Glorietta 1, Glorietta 2, etc. — each with a domed central area from which three floors of seven or eight aisles radiate like spokes from a hub.

The Visayan Islands

The Philippines is often mentioned as having three main areas: Luzon to the north, Mindanao to the south and the Visayan Islands in the middle.

The next morning our ride to Manila’s domestic airport took 30 minutes. Our flight to the town of Kalibo, in the province of Aklan in the western Visayan Islands, was 55 minutes. It then took two hours by bus to get to the Caticlan Wharf for a half-hour catamaran ride to Boracay Island.

Transportation to Boracay is by catamarans, which are motorized and canopied. Their bamboo outriggers extend out about 15 feet to both sides in an arc like the tip of a fishing pole being drawn to the water by a large catch. Four or five bamboo poles are required on each side, and from a distance the boats look a little like giant water spiders.

Boatmen charge 20 pesos (less than 50¢) per person, one way, to Boracay. We chartered our boat for about $15 and scrambled aboard onto the benches which ran the length of the narrow boat. Life jackets were donned and the boat’s solo crewmate steered us to sea.

At the wharf in Caticlan I had purchased some cheap sandals, which now came in handy since it was necessary to wade ashore. A useful local word here is magkano, meaning “How much?” in Tagalog. Most everything was marked up quite a bit and we were expected to bargain. If the asking price was 100, I’d offer 60, then settle on 80. If you learn to ask “How much?” in Tagalog, the dialect spoken in Manila, you’ll get a better price.

Boracay

The water was shallow and warm, and we all strode, MacArthur-like, to the beach and up to the Boracay Regency Resort (phone 63 36 288 6111) for lunch. It was newly built on the site of a previous resort which had only primitive bamboo huts called nipas covered with banana leaves.

Lunch consisted of steamed white rice with chicken cooked in a delicious mixture of vinegar, soy sauce and garlic. A chilled San Miguel beer was my choice of beverage.

In March the sun shone hot, and without sunglasses the glare was near blinding, but gentle winds made the temperature agreeable in the shade. In fact, March and April is the hot season here, but by the beginning of May it starts cooling down. Then come the typhoons in June and July.

The peak tourist season is from November into May, but due to the modern convenience of air-conditioning, the resort (as all others) is open year-round.

Low rates are offered at the Boracay Regency for the “lean season” (30%-40% discounted), while in the “super peak” season, during Christmas or Easter week, they add a surcharge of 10% to the standard rate. With 85 rooms total, standard rates for their smallest rooms start at just over $100 a night. An air-conditioned, 2-bedroom suite, sporting a lanai and suitable for a family, normally costs about $300 a night with breakfast daily. All rooms are furnished with bamboo and rattan furniture, cable TV and mini-bars.

After lunch we sailed up the shoreline to the Pearl of the Pacific Resort (White Beach, Boracay Island), where we spent the night. The lobby, the restaurant and bar were close to the water, while the rooms were in back of the road tucked into the hillside gardens.

All told, they have 60 rooms and suites, starting from about $100 a night during low season ($120 in high season, $140 in peak season) to $400 a night for a suite in high season. I found my standard room large and comfortable with all modern features, including color TV with CNN and a partial view of the sea through the palms.

Island atmosphere

One of the websites devoted to Boracay Island describes it as “a tropical paradise — crystal-blue waters, powder white sand, liberal doses of tropical palms and flowering plants, and a healthy marine life underneath the seas.”

I agree with most of that, except I thought the sand was really more the color of coffee, heavy on the cream and garnished with a sprig of parsley.

Algae was abundant at the warm, shallow water’s edge, and every morning the sea and the sand were separated by a ribbon of washed-up green. One resort challenged this by hiring a worker to come out early every morning to rake up the algae and groom the sand, but most simply let Mother Nature take care of this minor imperfection.

Going out for dinner, we hired “tricycles,” as we now called the Suzuki motorcycle taxis, for less than a dollar. I sat in the front and two others sat in the back. Their weight tilted the contraption, lifting its front wheel off the ground. As we drove, the driver and I leaned forward to give the guiding wheel some traction.

Tragedy strikes

On Tuesday, March 4, a terrorist blew himself up at the Davao City airport on Mindanao Island, taking 21 people with him. Until then, Davao had been spared the events that had harmed other areas of the south. Everyone was stunned, but life went on.

I asked a native his reaction. “It was a tragedy,” he said, “but tourism is vital to our economy so we must remind people that most of the Philippines is safe.”

One last day at Boracay

After breakfast we again hired “tricycles” and motored a couple of miles to the Pink Patio Resort (phone 632 845 2222) for our last night in Boracay. With 46 rooms, it is clean and modest with some of the trappings of a spa, including a nice pool and a rock climb. The resort is rated “AA” by the Department of Tourism — a single “A” is equivalent to one star, “AA” is like three stars, and “AAA” is like five stars. The cost was about $100 a night.

To get to the beach, I walked through an alley-like walkway. Along the beach’s edge is a sandy path which fronts dozens of stalls selling T-shirts, suntan lotion, sarongs and swimsuits. The many open-air bars and inviting restaurants were well patronized, and in the heart of this good-sized village is “D’ Mall,” an attempt to commercialize the shopping area.

I enjoyed an excellent lunch at Le Soleil de Boracay (phone 036 288 6209), a neat beachfront hotel.

On my way back to the Pink Patio, I noticed a sign advertising an English tea and pastry shop. There I spent an hour enjoying a pot and some banana nut bread for just over a dollar.

Returning to Manila

After an hour’s flight back to Manila, we traveled back to Makati via the Malate district, which is a little less fancy with its down-to-earth cafés, bars and bistros. This is where the café crowd hangs out. The area used to harbor Manila’s red-light district, but in 1992 Alfredo Lim was elected mayor on an anti-crime platform, including the promise that, if elected, he’d “close all the houses and nightclubs.” Many were skeptical, but he made good on his promise, essentially cleaning up the place.

Having stayed at the fabulous Peninsula and visited the luxurious Westin Philippine Plaza for lunch, I thought I’d seen it all. But our last hotel, the Makati Shangri-La (phone 632 813 8888), was every bit as stunning.

Our dinner was in the hotel’s French restaurant, Cheval Blanc, and we got to meet the skilled and inventive chef, a young American named Chris Romine. He graduated from the Pittsburgh School of Culinary Arts and has been on an odyssey since, looking for the perfect menu. I believe he found it.

He calls his dining creations, which are a harmonious melding of French taste, smell and style with some of the color, texture and accents of Filipino food, “French Fusion.” We felt honored by his selections and his attention to the details of our evening.

(Note: Cheval Blanc has been replaced by the recently opened Red. Chris Romine still presides as chef.)

A stay here is reasonably priced compared to equivalent hotels in America or Europe. During March, April and May they offer a great deal for $210 a night, including an automatic upgrade to a Premier Suite, complimentary airport transfers by limo and a scrumptious buffet breakfast.

A Philippine plantation

It was my last full day in the Philippines, and there was much more that I wanted to see. I became fascinated with the idea of seeing the Banaue Rice Terraces, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, but it was an 8-hour drive one way — too far for the little time I had left. Fortunately, our guide had arranged a day trip to a self-contained working plantation just 50 miles southeast.

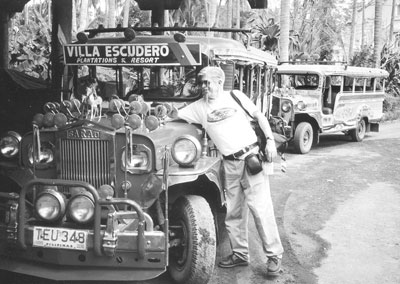

In our nonstop chartered van, the ride to Villa Escudero Plantations & Resort (phone 521 0830) near San Pablo City took about 1½ hours. The villa is one of the last of its kind and dates back to the 1860s. It was once part of a vast jungle owned by a native chieftain who had 29 wives, but, because of difficulties in supporting his extended family, he sold part of his land to Don Placide Escudero. Mr. Escudero invited six families to work and live on the plantation, and today there are a hundred families who have their own village near the main house.

At first the plantation grew sugarcane, then coconuts. In the 1970s, because of the steady decline in the price of coconuts, they started looking for alternate sources of income, and in 1981 they opened the plantation for public viewing and welcomed their first guests. With 400 regular employees, including those who still live on the plantation, they offer 32 cottages for overnight visitors.

The property can be reached by taking a left turn immediately past the “Welcome to the Province of Quezon” arch that spans the highway. Flanked by coconut trees, the road leads to a meadow. On the right, a collection of military weapons like airplanes, tanks and cannons can be seen. On the left, just a few hundred feet away, is a gorgeous church built in 18th-century style.

An ox-drawn passenger cart took us on a 15-minute tour of the village while a guitar player and two young ladies serenaded us with native songs sung in sweet-sounding harmony from the back of the vehicle. When we arrived at the church, the most beautiful one from the outside that I’d seen in the Philippines, we learned that it was never really a church at all but was built just 12 years before as a museum to house and display accumulated belongings of the Escudero family.

Of the museums we visited on this trip, I found this the most interesting. Initially, upon entering, it looked like someone’s jumbled and cluttered attic, stuffed with religious art and artifacts. Then came the natural history section with pin-mounted insects, stuffed animals and reptiles. Next were paintings of the indigenous peoples of the various regions of the Philippines.

This was a friendly museum, without apparent theme, displaying dolls, currency, ceramic pottery and an archaeological collection that included a smattering of early Greek and Roman tear vials uncovered in Egypt.

Visiting this place was a lot like rummaging through an antique store with a little bit of everything. Generations of Escuderos have contributed items like busts of family members, old love letters, high chairs once used by their children, discarded furniture and period clothing (some from famous citizens), ending with examples of military weapons and uniforms.

An unusual dining experience

Our buffet barbecue lunch at Villa Escudero Plantations was held in the river — yes, in the river! The family built a small hydroelectric power plant here years ago, and when the plantation was converted into a resort, someone came up with the idea of placing picnic tables and benches in the water just below the spillway where the riverbed had been leveled and paved.

Everyone had to take off their shoes, roll up their pant legs and wade in. The water was mid-calf deep and pleasant. Some children came prepared with bathing suits. It was a very unique setting for a meal, eating while dangling our bare feet in the running water.

Members of the plantation put on a pageant of folkloric dancing and singing to conclude our afternoon.

The plantation offers day tours which include a welcome drink, lunch at the waterfalls, a tour of the museum and the rural village and a cultural show. The cost for adults is 840 pesos ($15) weekdays and 950 pesos weekends.

Old Manila

We spent that evening in Intramuros, the old section of Manila. Intramuros, or Old Manila, is a walled city which was surrounded by a moat, in the medieval fashion, before being captured by the Americans. Partly to control malaria, the American army filled in the moats and made them into a golf course. With the walls complete and the beautiful course encircling it, the prospect of the town is magnificent.

Inside, the Old City has suffered some from its confinement, in addition to damage from earthquakes, fires, typhoons and World War II, but is now going through a renaissance. In the evening, outdoor musical entertainment is offered, and areas that were once dark are now well lit and populated by enticing restaurants.

One place here well worth a visit is the Casa Manila, a “colonial lifestyle” museum constructed in 1979. It was modeled after a 19th-century house in San Nicolas, a district across the river. My grandfather served under Dewey in the 1890s, and I imagine he would have recognized the style.

The next day I returned home on PAL’s nonstop flight, which took only 12 hours to reach San Francisco.

Now that I’ve seen the Philippines again, I remember why it’s called the “Pearl of the Pacific.” It is a gem. English is spoken everywhere, and I believe Americans are liked and welcome there.

Historically, it is a friendly nation that earned its independence and deserves our understanding and cooperation. It offers dozens of good reasons to visit, all for a good value.

*As a travel agent, I use services such as www.intelliguide.com and www.ijet.com to assess the risk of visiting a particular destination for my clients. Both of these services are available by subscription only. While both are aimed at the travel professional, iJET does offer services for the independent traveler. — S.V.

Steve Venables was a guest of the Philippine Department of Tourism (30 N. Michigan Ave., Ste. 913, Chicago, IL 60602; phone 312/782-2475).