An African-style safari...in Bolivia

by Diane Powell Ferguson, Scottsdale, AZ

I kept telling my husband, “You’ll love Bolivia,” and practicing Quechua on the dog. My other half remained skeptical while the dog became increasingly enthusiastic, since intonations of “Waliq alqu” (“Good dog”) were accompanied by continuous predeparture treats. We wanted to experience Bolivian history and wildlife but particularly emulate the “safari feel” we enjoy in Africa — without traveling quite as far.

Customizing a trip

The preliminary task was identifying travel operators offering the right combination of culture and adventure. The “Rough Guide to Bolivia” listed a Colorado-based company, Explore Bolivia (2510 North 47th St., Ste. 207, Boulder, CO 80301; phone 877/708-8810 or phone/fax 303/545-5728 or visit www.explorebolivia.com), which was able to support precisely that mix. The owner, Sergio Ballivian, is Bolivian and prides himself on designing traditional vacations as well as custom-tailored journeys. (Note: there is a Bolivian company of the same name that is no longer affiliated with the U.S. outfitter.)

We customized one of Explore Bolivia’s scheduled 8-day departures to the Beni pampas and Madidi National Park. In 2003 the price averaged $1,195 per person for three or more. We doubled the time in country to blend such diverse interests as colonial churches and pre-Incan ruins with wildlife viewing in the pampas and Amazon Basin.

The total land cost for our 16-day July tour was $2,550 per person. This included private English-speaking guides in four locations (La Paz, Sucre, Pampas and Madidi); drivers for touring and private transfers for eight air or boat departures; fifty percent of our meals (all meals for the week at the wildlife lodges and prepaid lunches in Sucre); one internal flight, and overland or river transport.

Sergio made special arrangements for a single guide to escort us from the pampas to the jungle, ensuring continuity of our wildlife experience.

We worked with Sergio for several weeks in advance via e-mail and telephone to plan each segment: four nights in La Paz, three in Sucre, two at the pampas and five in Madidi. We made special requests, including a day visit to the Tiwanaku ruins near La Paz and excursions to Tarabuco’s Sunday market and the dinosaur tracks near Sucre, plus guided boat trips and walks to find wildlife.

Our pretrip research revealed that the Bolivian pampas and rainforest ecolodges were not as developed or comfortable as what we have experienced in Africa. Although built within the last five to seven years, they are in remote areas and focus on delivering basic room and board with prime access to wildlife.

We specifically asked Sergio to recommend the best lodging per area as well as the most private and quiet accommodations available in each. Sergio travels to Bolivia frequently, so he personally inspected and reported on the remote lodges in advance of our trip, allowing us to choose the ones best suiting our needs. There was no extra charge for this direct attention to our request.

La Paz

Altitude was an issue for us, and we kept in mind that Bolivia’s capital, La Paz, sits at over 10,000 feet. Many of its newer, more modern hotels are located just east of downtown at over 11,000 feet, and trips to/from the airport involve another 1,000 feet in elevation gain.

We chose the 5-star Hotel Europa (Tiahuanacu 64) for its amenities and central location, within walking distance of sights, shopping and eating yet a street away from the main Prado for greater peace and quiet.

Our La Paz sightseeing included major churches, particularly San Francisco, whose Baroque exterior immediately evoked the feeling of Spain. We visited an interesting group of small museums on Calle Jaen, the latter’s Spanish colonial architecture a clear remnant of the past.

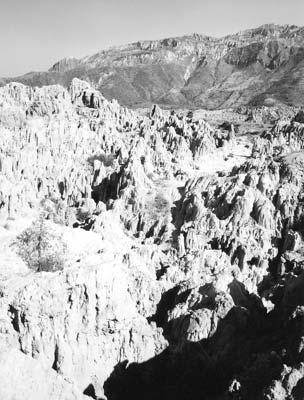

Outside La Paz, we drove to Valle de la Luna (Moon Valley) to photograph its weirdly eroded rocks and to Tiwanaku (or Tiahuanaco), site of a pre-Incan empire. While interesting, the ruins are neither as extensive nor as monumental as we had imagined, and they did not compare to pre-Incan sites we have visited in northern Peru.

Sucre

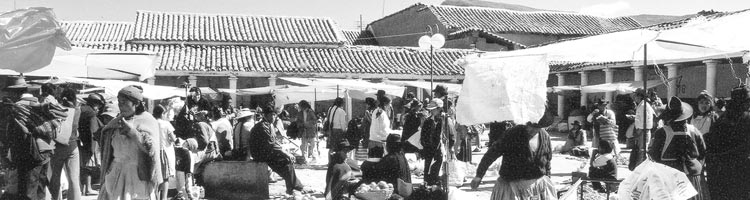

The next stop, Sucre, was chosen for its Spanish colonial heritage and architecture as well as its proximity to Tarabuco and Cal Orko. The town of Tarabuco, over an hour’s drive from Sucre, hosts a lively Sunday market. However, it is smaller than, for example, Ecuador’s Otavalo market, with fewer diverse goods. The prized weavings that made it famous were of average quality; many had been exposed to the sun too long, as witnessed by faded stripes that appeared when the pieces were unfolded.

An extensive, albeit more expensive, selection can be found in Tarabuco’s museum shop and at Sucre’s excellent Museo de Arte Indígena, a stunning showcase of traditional textiles and costumes.

Cal Orko, a few miles from Sucre and accessible via special “Dino-Truck” transport from the main plaza, displays the world’s largest known collection of dinosaur footprints. Formed 65 to 85 million years ago, they are now cliff-side pockmarks, having been lifted into a vertical position during the creation of the Andes.

Our Sucre hotel was the 3-star Paola Hostal (Calle Colón #138), noisy and without heat but centrally located a few blocks from the plaza and most sights. Many area hotels share the same busy streets. Since the local university boasts over 26,000 students, there was traffic all night long.

Although we were on our own for dinners in Sucre and all meals in La Paz, the exchange rate was US$1 to 7.70 bolivianos, and multicourse lunches or dinners rarely exceeded $4-$5 per person. We were frankly surprised at how well one could eat for so little.

Beni pampas

We returned to La Paz for our flight to the starting point of our pampas and Madidi excursions, Rurrenabaque. “Rurre” for short, it is a small, frontier-style port on the Beni River. Having little to hold our attention, it served primarily as a transfer point to Bolivia’s Amazon Basin. The top hotel, the 3-star Safari, offered us superb food, but its rooms needed a face-lift as well as hot water for showers.

We drove overland a dusty three hours and took a brief canoe ride to reach the Beni pampas. Our Yacuma River base was the Caracoles Refuge, one of only two or three local camps offering anything better than fly-tent lodging.

The refuge had several dormitories sleeping up to 10 and three or four “private” rooms sharing upper-screened walls with adjacent rooms. Our narrow quarters slept two in separate, mosquito-netted bunk-style beds. A table, chair and candleholder rounded out the spare furnishings. Guests share pairs of newly tiled showers and baths located in another building. The food was excellent, and the 3-course meals were eaten in a screened dining room.

The wildlife here was the draw for us: capybaras, caimans, pink river dolphins, several types of monkeys and a plethora of birds, including egrets, kingfishers, storks and vultures. Two to three times per day, we rode in canoes to search the river for animals. The appearance of reptiles or birds every few feet gobbled film quickly. We also did some walking and fishing and took night canoe rides to hunt for wildlife.

Given the time required to reach the pampas, any stay of less than two nights is not worthwhile. In order to track anaconda or any wildlife more than two hours from camp, three or more nights would be preferable. For the enthusiast, the Beni pampas offers extensive wildlife viewing, with greater ease and access than even the nearby rainforests.

Madidi Park

For the journey to Madidi Park, we returned to Rurre, from where boats typically leave in the morning. The trip is five or more hours upriver, first on the Beni River and then the Tuichi. Since the water is shallow, crewmen often pole through the low sections.

Once docked, we walked a half hour to Chalalán Ecolodge, a joint project built by the local community and conservation groups. Situated inside the park, it offers Andes and Amazonian ecosystems, including 700 species of animals and over 600 species of birds. Guides speak Spanish and English.

Available accommodations were either small buildings of rooms sharing partially screened walls or a few private cabanas. We enjoyed the honeymoon cabana, accessed by a private path, with its own porch hammock and chair. Shared baths and showers were clustered at either end of the compound.

Chalalán offered guided or independent wildlife walks along nine different trails. The dense jungle made finding animals hard, but our 16 hours spent traversing the park rewarded us with a number of sightings, including a rare blond anteater, a peccary and a poison dart frog. Our guide, Sandro, recognized and could mimic every beep and cheep. His extensive knowledge of plants, with their practical and medicinal uses, and exotic animal behaviors gave life and interest to what the untrained eye might view as just trees and sounds.

Bolivia is still developing its wildlife areas and supporting tourist infrastructure, but we were pleased with our south-of-the-border safari, enhanced by an introduction to Bolivian art, culture and history.