West Africa: from Bamako to Timbuktu and on to Dogon country

by Jim Sill, Silverado, CA

Intrepid travelers begin their overland journey through West Africa in Mali

Culturally rich and diverse, West Africa is a unique place for the adventure afforded by independent travel, offering unusual places to visit and cool stuff to buy.

My January-February ’07 visit added a fresh perspective to my 62 years of life experience that only Africa could provide. It was about experiencing minority status in a place unlike that where I live. It was about seeing natural wonders juxtaposed with humanity in the raw.

I wanted to experience life in West Africa firsthand in order to provide perspective on my other travel experiences, to appreciate the lifestyle I enjoy at home and, if I were lucky, to grow a little wiser.

Bamako, Mali

After about 18 hours of plane travel, the touchdown at Mali’s international airport in Bamako was dark, hard and sudden.

Upon descending the portable stairs in the middle of the runway, my travel companion Jenna and I found ourselves in the main terminal, a small, cramped room of crowded chaos. Several hundred of us formed queues, sort of, while yelling porters and others pushed, shoved and jammed themselves in around us.

Off in the corner was a small window for money exchange. Change some money there before entering Customs or later you’ll find yourself out on the street with a hundred taxi drivers screaming in a babble of Bambara and French and no other source for local currency.

Of all the men milling around, one spoke English and he helped us arrange for a taxi to our hotel. As he rode with us, he offered his services as a guide.

He said his name was Ibrahim, that he spoke six or seven different languages, was relatively fluent in English, was familiar with the areas we wanted to visit and had 10 years’ experience as a guide.

In Mali, I felt we would need a guide to get us to the relatively remote destinations and help us communicate. In Dogon country, for example, most of the villagers speak local languages only.

When we got to our hotel, we wrote out a day-by-day contract specifying what would be covered by the agreed-upon $1,900 fee: a week’s worth of guide services, a 4-wheel-drive vehicle, a driver, all food and accommodations.

I took a deep breath and gave Ibrahim $100 to seal the deal. He would meet us on the second morning for our trip to Mopti, our launching point for visits to Timbuktu and Dogon country.

A questionable purchase

Our first order of business was to change money. We walked to the nearest bank and got our first big surprise. Although several sources I’d checked on the Internet while researching our trip indicated that the U.S. dollar fetched roughly 600 CFAs, by the time we arrived a few months later the dollar had taken a dramatic downturn in that part of the world and we were offered only 465 CFAs. The rate was lower in smaller cities, and in some places they just didn’t want the U.S. dollar, preferring the euro instead.

Cash in hand, we took a taxi to Bamako’s Marche de l’Artisanat. This artisans’ market is a honeycomb of small shops, each displaying masks, carvings, leather goods and other handmade products. Artisans carved and whittled in the shade of a broad overhang around the periphery while shopkeepers and hustlers approached us at every turn.

As we made our initial walk-around to see what was there, we were repeatedly approached by a pair of hustlers who tried first to befriend us, then to be our “guides,” then to sell us stuff. We politely declined their offers, but they kept reappearing.

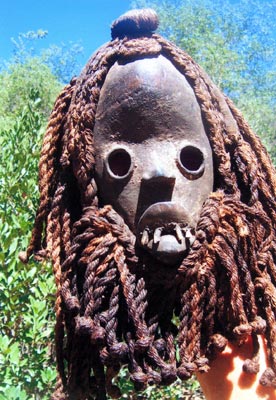

“Hey, you gotta see this,” said Jenna coming out of a mask shop.

I went in to look.

“I didn’t want to show you this,” she said, referring to a mask. “I don’t like the vibe, but I thought maybe you might like it.”

I needed that mask. It was real nasty-looking.

I haggled with the shopkeeper over it, walking out a couple of times, and soon it was mine. By the look on her face, Jenna was not pleased.

A harrowing experince

After a few more purchases, we walked over toward the fetish market. The same two hustlers approached us again, becoming more persistent. Again we declined.

Bamako’s fetish market is one of the saddest sights I’ve seen. Stall after stall displayed the heads, feet and bodies, rotting in the sun, of every animal imaginable — monkey heads, dog heads, crocodile heads and various reptilian feet and legs. A jar of porcupine quills flanked a row of dead parrots laying on the ground. The fetid stench of decaying flesh hung heavy in the air.

Juju, West African magic, and fetishism, a manifestation of it, underlie spirituality here, with believers attributing supernatural powers to fetishes of various kinds. They buy what a shaman believes might be the appropriate symbol to dispel their particular problem. The shaman then takes the body part, sprinkles it with the blood of a freshly killed chicken or other animal and — voila! — a barren woman can become pregnant, a man seeking revenge for an insult can inflict harm on the perpetrator, or a sacred place can be cursed with death for all who stumble upon it.

We then walked toward the main market, a sensory overload of car horns, clucking chickens, shops and makeshift stalls spilling into the street, pulsating with hundreds of people weaving their way through it all.

I could feel their presence behind me. “You owe 15,000 CFAs for all our time,” demanded one of the two men who had been following us.

I turned around. “I want nothing from you.” As I turned, one of them tried to trip me from behind.

“Leave us alone!” cried Jenna. “We’ve done nothing to you.”

“We ha’ no problem wi’ you,” the other man said, “but this man no good. He no like black people.” He stepped on my heel.

“If I didn’t like black people, I wouldn’t have come to Africa,” I said, realizing we were kind of beyond the point of rational discussion.

We headed into the bustling crowd and crossed the street to try to get away from them. They continued to follow us closely. Then, out of the dust and bustle, a taxi appeared. I stepped in front of it, pushed Jenna inside and got inside, myself. We were safe.

On the road to Timbuktu

Ibrahim, our guide, was right on time at our hotel the next morning with a land cruiser and an affable driver named Amadou. After stopping to gas up and buy a case of water, we were on our way to Mopti, Mali’s central city on the Niger.

We rolled into Mopti about 9 p.m., got a hotel room with seemingly more mosquitoes inside than outside and prepared to go to bed. Suddenly, there was a knock on the door. I answered it, and a hand with an aerosol can of mosquito repellent jutted into our room. A voice from down the darkened hall said in pretty good English, “You’ll need that!”

I took the can and sprayed the hell out of the room before crawling under the mosquito net fully clothed.

Ibrahim had us up and out the door by 6:00 the next morning. We drove on asphalt until about 9, stopping for café au lait and croissants at a village truck stop. The French left a lovely legacy of gastronomic savvy which, when combined with the local cuisine, results in some pretty tasty fare. Before we left, I noticed Amadou fussing over the left rear tire.

We drove a few miles more, then turned off the asphalt onto a dirt road which quickly deteriorated to washboard rivaling the worst that Baja California has to offer. Then that rear left tire went flat. Amadou put our spare on and we were back on the road again.

After about an hour there was a loud bang from the left rear. Amadou got out and I could see his face as he looked at the spare tire; it was the look of a man who had just lost the lottery by one number. There was no second spare.

We waited by the side of the road, then Ibrahim flagged down a passing land cruiser and he gave us his spare. We were on our way again.

We reached a ferry crossing by about 4 in the afternoon and waited for the next ferry. More and more vehicles lined up behind us. I was surprised at the number of vehicles — and the number of white people — there, it turned out, for Le Festival au Desert, an annual 3-day music festival celebrating West African music and held at an oasis about 60 kilometers outside Timbuktu.

As the ferry appeared, I noticed Amadou and Ibrahim in a heated discussion — next to the left rear tire. The spare that we had borrowed was flat. As the ferry pulled in, the cars in back of us swerved around us and drove onto the ferry while Ibrahim frantically looked for another tire. By the time he found one — so bald that you could almost see your reflection in it — the ferry had left and we were last in line again.

I looked at Jenna and she shook her head. “It’s that mask,” she muttered.

Some more bad luck

Somehow that baldest of all tires held long enough to limp us into Timbuktu about 9 p.m. Ibrahim directed Amadou to a hotel that he knew of. Ibrahim went inside for a moment and returned.

“It’s full. I know another one,” he said.

But that one was full, too. We went to others. They all were full.

Jenna gave me the look. I turned away, pretending not to notice.

Ibrahim stopped to talk to some locals, and soon we were on our way to a private home. We wound up sleeping on mats on a mud floor. The toilet outside was typical of the area, consisting of a hole in the ground, blue sky above and a small teapot with water next to the hole. If you wanted a shower, you filled a bucket with water from the urn outside the bathroom. If you wanted toilet paper, you brought it with you.

The next morning we moved to Hotel La Colombe (phone 292 14 35), a clean, centrally located hotel with hot water, a firm bed and a killer view of the Sahara ($40 a night for a double).

Frankly, we were disappointed with Timbuktu. I don’t know if it was because of all the tourists who had flooded in for the festival, but it had kind of a jaded vibe to it.

Back to Mopti

We left early the next morning. As we swung onto the “road” through the desert, I noticed that Amadou was driving in the sand next to the road, apparently to preserve the latest rear left tire. Soon the rear wheels began to spin and sink, almost to the hubs. With one more try at escape, Amadou buried the truck up to the chassis.

We tried for two hours to free the truck, all to no avail. After another half an hour a convoy of trucks approached. Everybody, including the Korean tourists inside, came over to help push our truck out of its grave.

I noticed this willingness to help throughout my trip. Africans helped each other, even when it took a lot of time, even when it was really inconvenient.

After about 15 minutes, we were on the road again.

By late afternoon we reached the paved main road back to Mopti. We stopped for a late lunch of yassa poulet (roast chicken with a caramelized onion sauce) at a small truck stop.

As we ate, a group of young boys gathered outside the fenced patio where we were eating and watched. Jenna finished her chicken, leaving only skin and bones and some gravy. One of the boys said something to Ibrahim, who looked at Jenna and asked, “Are you finished? They want the bones.”

Jenna nodded and raised her plate to give it to them and little hands darted over her shoulder, snatching at the plate. Chicken bones flew everywhere. In a splattering instant, the plate was bare. Ibrahim was nonplussed. Jenna and I were shocked.

Back at Mopti, we stayed at a French-owned hotel called Y A Pas De Probleme (phone [00 223] 243 1041, www.yapasdeprobleme.com), a very popular place with Europeans passing through Mopti, where a room with a good mosquito net and hot shower cost about $40 a night. The rooftop restaurant offered excellent African and French cuisine.

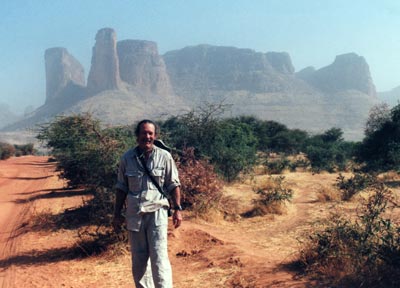

Dogon country

The next morning we departed for Dogon country, Mali’s premier tourist destination. It’s located on the Bandiagara Escarpment, a monolithic plateau stretching 150 kilometers (93 miles) with sheer cliff faces honeycombed with caves and recesses into which an ancient people built extensive cities similar to the pre-Columbian Anasazi of Mesa Verde in Colorado, but on a much larger scale.

Today, the Dogon use the cliff structures for ceremonial purposes but do not live there, choosing instead to live on their farms on the plains above or below.

We first visited Djiguibombo, a high-plains village of mud homes with thatched roofs, spending some time with the village elders. We handed out kola nuts, a custom of visitation among the Dogon, then moved on to the next village, Kani Kombole, where we were warmly greeted by Ajumah, the chief, who squealed in falsetto when we handed him kola nuts.

Ajumah made us feel welcome by personally showing us his carefully laid-out arts-and-crafts showroom, bringing out tables and chairs so we could have tea and inviting us to spend the night on a rooftop. We accepted his invitation.

I noticed how the villagers all were pretty friendly, which Ibrahim attributed to Ajumah’s leadership.

Our experience there stood out in contrast to the less-hospitable vibe we found at the nearby village of Teli, whose chief appeared to be drunk and was particularly loud and obnoxious.

After a pleasant night in Kani Kombole, waking to a cacophony of farm animals, we returned to Mopti where we would spend one more night before embarking by bus to Bobo-Dioulasso in Burkina Faso.

Pick your climate

When you travel through West Africa, you have a choice of three climates.

Winter offers relatively cool temperatures but brings a weather phenomenon called the Harmattan, winds that blow out of the northeast Sahara carrying dust with the consistency of confectionary sugar. They are most pronounced during December and January, tapering off through March as the weather turns hot.

The dust can be so thick as to limit visibility to no more than 150 to 200 yards. Both Jenna and I developed a respiratory malaise characterized by cold symptoms that included a cough, stuffy nose and sore throat from inhaling so much dust.

March through May is dry and hot, with temperatures typically topping 105°.

June through September constitutes the wet season, with monsoonal rains plus winds up to 70 mph. During this time, the sub-Saharan Sahel turns from a drab, dusty brown to a lush green, with rivers roaring and mosquitoes soaring — along with the number of malaria cases and other mosquito-spread diseases.

As the wet season tapers off, September through November moves into the early dry season. Harvests are taken and mosquitoes continue to breed like crazy.

Next month, the journey continues with a bus ride from hell.