Interpreting the past in the Vasa garden

This item appears on page 80 of the April 2008 issue.

by Yvonne Michie Horn

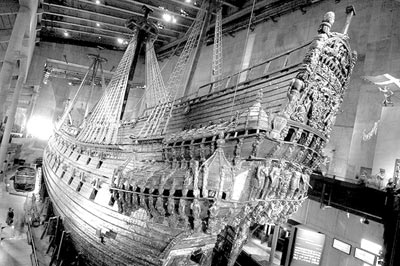

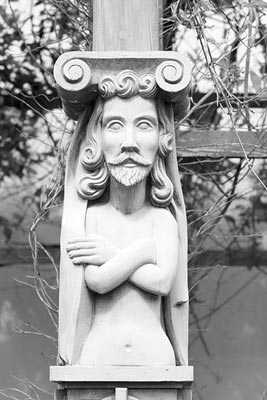

The Vasa was a magnificent ship. Decorated with symbolic sculptures and carvings, gold leaf on her poop and bronze guns polished to a fare-thee-well, she was built to impress and strike fear as the pride of Sweden’s 17th-century Royal navy.

On a fine August day in 1628, with king, court and populace gathered, she was launched. Within minutes — sails set, flags flying, gun ports open for the royal salute — she caught a gust, heeled over and sank.

The Vasa lay in Stockholm harbor for 333 years. In 1961 she was brought up from centuries of enveloping mud. With the salvage came skeletons of the drowned along with some 24,000 preserved objects.

In 1990 the Vasamuseet, located less than a nautical mile from the spot where she capsized, opened to display her restoration. The museum — with its interactive exhibits and films that bring to life the Vasa and her times — has become one of Scandinavia’s most visited attractions.

However, relatively few of the approximately 800,000 who come to the Vasamuseet each year find their way to a jewel of a Renaissance garden behind the museum. On an overcast June day, with the museum’s interior bustling with people, I found myself alone in the garden.

Genesis of the garden

The garden, overseen by the museum’s educational team, had its beginnings in the 1990s as a learning tool for groups of schoolchildren. Slowly it evolved into a reproduction of an early 17th-century garden and a permanent exhibit open to all.

“We grow the vegetables, medicinal plants and flowers that were cultivated by nobility and peasants alike during the time of the Vasa,” explained Ylva Lewenhaupt, one of two women charged with caring for the garden. “Items associated with food and medicine found on board the salvaged ship inspired the garden’s creation.”

Peas, for example.

“Dried peas, along with bread and ale, were staples for the crew’s diet,” Lewenhaupt told me. “A terribly monotonous diet!”

Coming into sprout this day were blue peas of a variety that once contributed to that diet: botanical name pisum sativum ssp. arvense, grown from seeds procured from SESAM, Swedish Seed Savers, an arm of the Nordic Gene Bank, a prominent center in the global network for the conservation and use of genetic plant material.

“We search for the most original version of each species,” Lewenhaupt continued. “That is why we have, for instance, white and yellow carrots (Blanche á Collet Vert and Jaune de Doube) and no ordinary supermarket orange carrots. And this cabbage, in Sweden the variety was lost. Detective work uncovered it in a St. Petersburg gene bank and now it grows in our garden.”

A learning experience

Signage, with English translation, invites lingering and immersion into the past while carrying forth the garden’s educational message. “In the month of May,” I read, “you must fertilize your cabbage patch and plant enough cabbage to last the whole year” — 16th-century Almanac.

The Medicine Garden section describes the severe hardships seamen suffered aboard the navy ships alongside plantings of the herbs dispensed by the barber/medicinal officer to cure and ease pain. “Fennel seeds boiled in water are beneficial for those who have the shivers” — from a 1620 herbal book.

Here, too, I learned that medicinal plants must be reaped at the proper time. “In springtime when the root is most potent or in the autumn when everything withers and strength returns to the root” — Swedish Housekeeping Handbook 1660s.

“The thing I love most about the garden is what it tells me about the past,” said Elna Nord, garden co-caretaker. “Each plant has a history, often with interesting details that put a human face on the species.”

Neither Nord nor Lewenhaupt claimed horticultural backgrounds, having inherited responsibility for the garden by default when its originator retired. Both are employed as curators for Sweden’s National Maritime Museums, of which there are three in Stockholm, with the Vasa one of the three.

“Both Ylva and I grew up in the countryside,” Nord said,”so we enjoy being out in the garden. And, yes, we are the ones who do all the work. It’s a nice break from the office and attending meetings!”

Thoughtfully organized

Flowers are present in the garden but sparingly so, as was the then custom.

“Rather than mass plantings, a single blossom was given its due,” explained Nord.

As typical in a Renaissance garden, a boxwood border emphasizes the tidiness of the flower area.

“The variety growing here came from a border growing in Sweden’s Castle Såstaholm’s garden,” Nord related. “An 18th-century document described it, even then, as a very old variety.”

Typical, too, of the time is an arched alleé, in this case covered with honeysuckle.

On the opposite side of the garden, a lush growth of hops clambers a series of poles. Signage told me, “Hop blooms spiced ale for the gentry, ale for the simple folk, ale for the captains and ale for the seamen,” ending with an admonishment that underlined the importance of hops through the ages: “If somebody should steal hops from the hops’ garden, he is to be taken to the Court House and judged” — Medieval Law.

As I left the garden, I carried with me a final quotation, not only struck by its aptness centuries later but by the fact that it was deemed important so long ago: “The earth is the most important thing we have. Be prepared to feed, fertilize and treat it well so that it will have the strength to repay its master for his toil” — Swedish Housekeeping Handbook 1660s.

For a visit

Where — The garden is located behind Stockholm’s Vasa Museum (Box 27131 SE-102 52, Stockholm, Sweden; phone 46 8 519 548 00, fax +46 8 519 54883 or visit www.vasa museet.se) at Galavarvagen 14 on Djurgården Island. The museum can be reached easily on foot, bus, tram or ferry.

Entrance fee — There is no charge to visit the garden. Admission to the museum is SEK80 (about $12) for adults; children under age 12 enter free. The museum is open 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. September through May and 8:30-6 June through August.

Tip — The museum is a Stockholm “must see.” Allow a minimum of two to three hours to do it justice. For the most meaningful experience, take in the museum before visiting the garden.

More to see and do on Djurgården Island — Once a royal hunting ground and now the city’s playground, the island offers a wealth of things to do and see. Bicycles, canoes, pedal boats and even rollerblades can be rented as ways to get around.

Tivoli Gröna Lund is an amusement park with roots in the 19th century. Fans of Astrid Lindgren’s books for children should not miss Junibacken, with its miniature scenes and the opportunity to meet up with Pippi Longstocking.

Skansen, with houses and workshops devoted to Stockholm’s early days, is the oldest open-air museum in the world.