Coping with and fighting poverty during travels

When my husband, Frank, and I planned our trip to India, we wondered how we would react to seeing people living in third-world slums or on the street, and to beggars, especially children. Would we feel so guilty about having the money to travel that we couldn’t enjoy our trip?

We spent a month, Jan. 19-Feb. 14, 2007, on a private tour of North and South India arranged by Nino Mohan of Worldview Tours (Newport Beach, CA; 800/373-0388, www.worldviewtours.com). The land-only cost was $7,090 per person, or about $250 per day, plus $1,580 for domestic flights. The tour price included some hotel upgrades but did not include tips, lunch and dinner.

Based on our experiences traveling to developing countries, we offer these tips for coping with terrible poverty while traveling.

Contribute globally

Before your trip, make a large donation to a nonprofit organization that does charitable work in the country you are visiting. As a guideline, we used the cost-per-day of the trip as our minimum donation, so for this trip we gave at least $500 to organizations.

Organizations like Habitat for Humanity (Atlanta, GA; 800/422-4828, www.habitat.org), The Heifer Project (Little Rock, AR; 800/422-0474, www.heifer.org) and the International Committee of the Red Cross (Geneva, Switzerland; phone ++41 [22] 734 6001, www.icrc.org) operate in many developing countries and will honor your request that your contribution be used in the country you specify.

Help locally

Should you give money to beggars? One guide gave us this advice: 1) Never give to children. It teaches them to beg. 2) If you give to one child, you will be surrounded by 20. Will you give to them all? 3) If you must give to a child, give only to the mother.

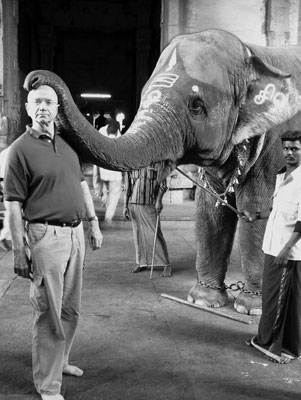

Early in our trip, in Sarnath, where the Buddha preached his first sermon, Frank gave coins to a man with an outstretched hand and was instantly swarmed by many other beggars. After that, we decided not to give directly to people begging.

To avoid the discomfort of not responding, I usually fiddled with my new camera, which kept my eyes and my mind busy. You must avert your eyes, because beggars may interpret eye contact as an invitation.

We noticed that they didn’t approach us as relentlessly when we stayed close behind our guide. Should you want to give to someone directly, you could ask your guide to identify people he or she is familiar with.

Donate to local charitable programs

Even if you don’t give money to beggars, you still can help the poor while you are there. We learned that, in India, many temples provide one free meal daily for anyone who is hungry. You can support this work, but you must ask your guide to point out the collection box in the temple specifically for this project. Any money you give to the Brahmin is his to keep personally.

You also can support temples’ work in a more unusual way, by buying “temple jewelry.” This is jewelry donated to the temple by members in thanksgiving for a prayer answered. Periodically, the temple board will decide to sell some of the jewelry to fund its activities. The jewelry is evaluated by the government and sold in retail stores. In Chennai, for example, you can buy temple jewelry at the Saga department store. Your guide can provide more information.

Near Khajuraho, our guide showed us the school where his wife taught. And, at the suggestion of Nino Mohan, we donated boxes of pencils and pens to selected schools. In Kerala, South India, which has a literacy rate of more than 90%, children and adults will request a pen or pencil instead of asking for money. We kept extras at hand during our excursions.

Learn

When you fly into Mumbai, you may come in over the Dharavi slum, Asia’s largest, with over one million residents. If you wonder how people live in these shantytowns, read “Shantaram “ by Gregory David Roberts (2003, St. Martin’s Press — ASIN 000OLDIM2).

Roberts is an Australian who escaped from prison there and eventually worked with the Mumbai mob. Although the book has many faults, the section describing the author’s two years living in a Mumbai slum lets you see the dignity, cooperation and organization of life there.

If you want to learn about the lives of the poor in India directly, you can arrange to take a tour of Dharavi slum in Mumbai through Chris Way and Krishna Poojari of Reality Tours & Travel (1/26 Akber House, Nowroji Fardonji Rd., Colaba, Mumbai 400 039, India; phone +91 98208 22253, www.realitytoursandtravel.com).

While some decry such tours as exploitive and voyeuristic, tour leaders suggest that travelers who see the poor as people like themselves are more motivated to help than those who observe from a distance. The Mumbai tour helps poor Indians learn that they can subsist not just by begging but can improve their lives by making products that people want to buy.

A source for education about and outreach to India’s poor is The Salaam Baalak Trust (2nd Floor, DDA Community Centre, Gali Chandiwali, Paharganj, New Delhi, 110055, India; phone 91 11 23584164 or 23589305, www.salaambaalaktrust.com).

Don’t forget what you saw and learned

Since our return from India, we have changed the traditions of our Christmas gift exchange. Now we ask relatives to make a donation to a charity for programs in India instead of giving us something. This way, the gifts of courage, grace and kindness we received from so many people during our trip stay in our hearts and, we hope, return to them.

We would be interested to hear from other ITN readers about how they respond to poverty on their travels in comments c/o ITN.

MARTHA SPRING

Albuquerque, NM