Cruising the NW Passage – a thrilling 32-day journey

This article appears on page 6 of the June 2017 issue.

“The Northwest Passage” — words that have excited Europeans for hundreds of years.

The quest for a navigable northern passage to deliver goods from Europe to Asia and return stimulated seafaring explorers to try and try again over centuries to sail through the Arctic from the Atlantic to the Pacific. Finally, Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen made the transit between 1903 and 1906 on a gasoline-powered converted fishing vessel. It wasn’t until 1944 that a ship made it through in a single year.

In the last 30 years or so, with the diminution of polar ice due to global warming, an increasing number of small cargo ships have made the trip, and in 1984 the Lindblad Explorer became the first passenger ship to cover the 900-mile transit.

Then, in August 2016 — 110 years after Amundsen — the largest passenger ship yet made the journey. The Crystal Serenity, a 68,000-ton, 13-deck ship carrying 960 passengers and a crew of 650, cruised from Seward, Alaska, up and over the top of Canada, eastward to the Atlantic and down past Greenland, ending in New York City 32 days later… and I was on board!

Safety first

Preparations for this record-setting voyage began three years before, when Crystal Cruises met with the US and Canadian coast guards to see if the cruise was practical and safe, not only for the passengers and crew but for the residents of the towns and villages located in the far north and for the environment.

Then Serenity’s captain, Birger Vorland, and his bridge staff attended a special 2-day training program for sailing and navigating in ice-filled waters.

Two ice searchlights, high-resolution radar and thermal-imaging and other equipment were installed to allow the Serenity to scan the waters, both ahead and below, for icebergs, obstructions or uncharted rocks. Its bridge team was augmented by two professional pilots who had decades of experience in Arctic waters.

The Serenity’s 820-foot-long hull was not strengthened for ice, but it had operated in both Arctic and Antarctic waters, and, in the event of excessive ice, the ship could call upon the ice-strengthened RRS Ernest Shackleton, a logistics and research ship belonging to the British Antarctic Survey, which would accompany Serenity during its voyage.

The Shackleton would also carry two 6-passenger helicopters, oil-pollution-containment equipment and survival rations for emergency use as well as the kayaks and Zodiacs (inflatable powerboats) that would take passengers to shore and on excursions.

Of course, the possibility of medical issues arising for passengers and crew had to be considered, as well. Because of the remoteness of the area we would be visiting, each passenger was required to purchase a minimum of $50,000 of emergency-medical-evacuation insurance. The helicopters aboard the Shackleton were available, if needed, to transport patients to an airport or medical facility onshore.

For nonemergency issues, the Serenity had a well-stocked medical facility, with two doctors and nurses.

For the upcoming August 2017 cruise, per-person prices, based on double occupancy, range from $21,855 for an ocean-view cabin to $61,090 for a suite.

Getting under way

Our trip officially began in Seward, Alaska, on Aug. 16. Each passenger was given a bright-red parka with a fur-lined hood, and we all were advised to bring high rubber boots, thermal underwear and whatever else we might need to keep us warm.

The first days of the cruise were filled with lectures telling us about the history of exploration in that part of the world and with safety talks about the use of the Zodiacs and kayaks… and about polar bears and wolves. There were historians, naturalists, ichthyologists, ornithologists, glaciologists and other “ists” on board to keep us well informed about what we were about to see and experience.

After leaving Seward, we visited Kodiak and Dutch Harbor, Alaska, then headed north across the Bering Sea to Nome. This was our first experience with bumpy seas — 10-foot swells and whitecaps. Topping off its fuel and loading last-minute provisions in Nome, the ship began its 4-day journey through the Bering, Chukchi and Beaufort seas on its way to Ulukhaktok, Canada.

Canadian ports

Sailing north, we encountered 15-foot seas, 70-mph winds and temperatures in the 30s as we passed the Arctic Circle on Aug. 21. It was gray and gloomy in the morning, but by the afternoon the sun was out, with light-blue skies, royal-blue water and white foam driven by the wind. Beautiful!

Soon the captain announced from the bridge that he saw pack ice ahead, and a little later I could see small icebergs on our port side. Our first ice!

As we continued through the Beaufort Sea, we passed the Smoking Hills on the east coast of Cape Bathurst. As rocks containing iron sulfide are exposed to the air, a heat-producing chemical reaction is created, igniting the surrounding hydrocarbon-bearing rocks and generating smoke. These rocks have been burning for hundreds of years, and the smoke was visible for miles.

As we reached our first Canadian port, Ulukhaktok in the Northwest Territories, a village of 415 people, we went ashore via Zodiac and were greeted with open arms by most of the populace. I’d guess this was the biggest event ever to occur in this village. Small expedition and scientific ships had visited in the past, but never anything quite as large as the Serenity. We were asked many questions and posed for photos.

The residents, predominantly Inuits, live in prefab houses. They get around on ATVs, bicycles and motor scooters and, in winter, when the temperature can drop to 30° below zero, on motorized sleds. Their diet consists mainly of seal meat and fish, although there was a general store carrying many of the same items that we have in our stores.

The Serenity crew did a marvelous job getting hundreds of passengers off and back on the ship smoothly.

In addition to the parka I was given, when going ashore I was prepared to wear long underwear, a shirt, sweater, heavy socks, rain pants, gloves, a hat and high rubber boots for the wet Zodiac landings, but I found on this first shore visit that hiking or just walking around kept me warm enough. So, for future shore visits, I substituted a lighter jacket and left the parka back on the ship, even though the temperatures were consistently in the 35°-39°F range.

I should note that when we went ashore at any of the Canadian ports, aside from visiting with the local residents, we could purchase art objects made by locals, including carvings of soapstone, ivory and bone and items sewn by hand. I acquired a wall hanging sewn by a local woman and had a chance to meet her.

We later learned that at one small village we visited, the ship’s passengers spent a total of $110,000 on that day — quite a boost for the local economy!

Passengers could also choose to take guided hikes, go kayaking or visit local churches and just walk around. However, we were all warned about the potential danger of polar bears and wolves and were cautioned not to go outside the village limits.

Those who went on hikes were accompanied by a man with a rifle, just in case a polar bear or wolf was encountered. I heard no stories of any meetings with any carnivores.

Spectacular sight

Internet access became more sporadic the farther north we sailed, and there were several days on which we had no communication to or from the outside world. The ship, however, maintained the ability to communicate in case of an emergency.

Up until 1999, Canada had 10 provinces and two territories, but the native Inuit people pressed for a territory of their own and, after a national vote, Nunavut was carved out of the Northwest Territory. Our next port was Cambridge Bay, located in Nunavut.

This town of 1,700 is the biggest port for vessels sailing through the Northwest Passage and is useful as a place to resupply (as we did).

Crystal had flown in a 737 with 25,000 pounds of food to carry us to our next resupply port, in Greenland.

On Aug. 30, as we sailed through Victoria Strait, looking forward to five days at sea until our next port, we came across our first sighting of major ice floes and icebergs.

This day became, for many passengers, one of the high points of the cruise, as we spotted our first polar bears! A number of passengers were able to board Zodiacs and get close enough to take photos.

There were, on separate floes, a single male bear, a mother bear with two cubs and a male bear eating a seal he had just killed. We spent several hours slowly drifting around the bears so the Zodiacs could return to the ship and pick up new passengers for their turn to get up close and personal with the bears.

That day, thereafter known as “Polar Bear Day,” must have been the subject of hundreds of emails sent out from the ship to relatives and friends back home.

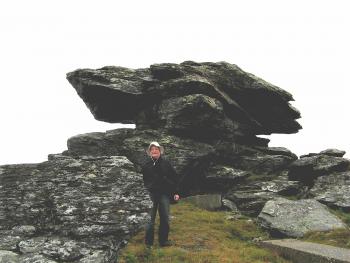

A couple of days later, on our way through Peel Sound, we stopped for a while to make some Zodiac landings on Beechey Island, where we found several memorial cairns on shore commemorating the sailors of a 2-ship expedition headed by Sir John Franklin that was lost in this area in 1845.

It was hard to imagine what it must have been like in those days, sailing on a wooden ship with no central heat and no engine, radar or radio.

The remains of one of the Franklin ships were found a couple of years ago, and, coincidentally, the second ship was discovered at the same time as we were on this Northwest Passage cruise.

Wild weather

Sept. 1 was a day of extremes. We were at latitude 75° North, the farthest north we would get on this cruise, and the temperature was the coldest we would encounter, 29°F. It was the first time we saw snow falling. A day to remember!

The next day we were in Croker Bay, and we went out in Zodiacs to view Croker Glacier, several hundred feet high and more than a mile wide. The sun came out and we saw every shade of blue in the glacier’s ice. Beautiful.

While we were out on the water, one of the ship’s Zodiacs came alongside with hot chocolate, which was very welcome on the 30°F morning.

We were admiring a large iceberg that had calved off the glacier when a baby harp seal broke the surface of the water and played hide-and-seek with us for a few minutes.

In this part of the world, the weather is very changeable. One morning, as we were anchored in Tay Sound, I was having breakfast and the sun was shining. The rocky hills 200 yards away were clearly visible, as were the snow-covered hills beyond. Then it clouded up and the water became gray; then the fog came in and the distant hills disappeared; then it began to snow and the nearby hills were gone; then the fog became so thick that I couldn’t see the water just below the window, and then the sun came out and away went the gray and gloom. All within 40 minutes.

Getting to Greenland

Pond Inlet, population 1,600, was our last Canadian port. A number of the locals were invited to come on board for lunch, and about 25 kids and adults joined us. You can imagine the wide eyes and smiles when they saw the ship’s lavish luncheon buffet.

A couple of days later we were sailing through the Davis Strait toward Greenland when we came across the biggest ice we had yet seen. Hundreds of brash ice, bergy bits and large icebergs were scattered all over the seascape.

The ship moved very slowly as we negotiated our way toward Ilulissat, Greenland, our next port. We were to anchor in the bay and use Zodiacs to go ashore, but the captain announced that, due to the heavy ice, we would be behind schedule as we approached our anchorage.

As the day went on, we were informed that the ice was solid more than six miles from shore, so it would not be possible to get to our scheduled port. That was disappointing, but, as any traveler knows, there are always bumps in the road, and one must be able to make accommodations.

We were able to get into Zodiacs and explore the icebergs and the edge of the pack ice that had stymied us. It was a worthwhile excursion for those who had not yet been up close to large icebergs.

Our next two ports in Greenland were Sisimiut and Nuuk. We picked up additional provisions in Nuuk, the country’s capital, and visited its small but excellent museum devoted to the native people who populated this area tens of thousands of years ago.

When we left Nuuk, cruising through the Labrador Sea, the feeling of accomplishment began to sink in. We had done in about 32 days what Roald Amundsen had taken three years to do so long ago. The transit was over, and as we entered the Atlantic Ocean, we gave ourselves a mighty cheer.

It was a great ride, covering more than 8,000 miles. I wish you had been with us!